Marta Mesias

Institute of Food Science, Technology and Nutrition, ICTAN-CSIC, José Antonio Novais 10, 28040 Madrid, Spain. Tel.: +34 91 549 2300; fax: +34 91 549 3627.

E-mail address: mmesias@ictan.csic.es

© 2019 Sift Desk Journals. All Rights Reserved

VOLUME: 3 ISSUE: 5

Page No: 450-459

Marta Mesias

Institute of Food Science, Technology and Nutrition, ICTAN-CSIC, José Antonio Novais 10, 28040 Madrid, Spain. Tel.: +34 91 549 2300; fax: +34 91 549 3627.

E-mail address: mmesias@ictan.csic.es

Marta Mesias*, Cristina Delgado-Andrade, Francisco J Morales

Institute of Food Science, Technology and Nutrition, ICTAN-CSIC, José Antonio Novais 10, 28040 Madrid, Spain.

sai(saikrishna2.info@gmail.com)

Mes

Deep-frying is a popular and ancient method of food preparation frequently applied within the industrial and domestic context. Although it is an important part of the Mediterranean diet, lately health authorities has recommended reducing the use of this culinary technique in order to follow healthier habits. Despite these recommendations, due to the current life style, fried foods have increased popularity because of its easy and fast preparation and their tasty appearance, that correspond to the wishes of the consumer. The aim of this work was to evaluate the domestic deep-frying habits and consumer’s preferences in Spanish households assessing the use of different kitchen appliances, type of oil used for frying, kind of food intended for frying, reuse habits of the frying oil and different habits for the frying procedure.

A questionnaire was distributed among 461 Spanish people mainly through schools, consumer associations, Universities, food associations, research centres, culinary centres, etc.

Results from the present survey revealed that fried food consumption in the Spanish population is similar to other Western countries, with the particular feature that olive oil was mainly employed. The most common appliance for the frying process was the frying pan (75.1% of participants), a fact favouring the frequency of oil change and the control of the frying temperature; electric fryer users (4.8% of participants) often left this variable uncontrolled.

Since fried potatoes, a product which can be a dietary source of certain chemical processing contaminants such as acrylamide, were by far the most consumed fried food (34.5% of participants consumed them once or more a week), futures studies evaluating the domestic frying of potatoes and consumer`s preferences would be interesting.

Key words: consumers, domestic habits, fried products, frying habits, households, oil

Deep-frying is a popular and ancient method of food preparation frequently applied within the industrial and domestic context[1]. From a chemical point of view, it implies a dehydration process characterized by a short cooking time due to the hot transfer, inner food temperature below 100ºC and fat absorption from the frying medium. The procedure involves submerging a food in extremely hot fat or oil (160-180ºC) that acts as hot transmitter to produce a fast and uniform heating. As the temperature difference between the heating medium and food increases, the heat transfer within the cooking process runs much faster. Simultaneously with the heat transfer, mass is transferred from the food to the frying medium and vice versa[2,3]. In a well done deep-frying, the final product will be hot and crispy on the outside and cooked safely in the centre[4]. In this way, it is possible to preserve many of the characteristics of the food, improving in most cases, its taste, texture, appearance and colour. It allows obtaining a more appetizing product, which undoubtedly contributes to the successful consumption of fried products[5].

There are substantial differences between the frying process from the industrial sector and that performed at the domestic environment and at restaurants or foodservices establishments. In the first case continuous processes predominate, replenishing fresh oil as it is consumed by the food and therefore oil is practically not discarded. In restaurants and fast foods establishments, the frying processes are discontinuous. The oil is re-used while its organoleptic and nutritional qualities are maintained, a fact determined using objective criteria (such as polar compounds index). In the households, the re-use of oil is a common practice, especially due to economic reasons, and its discard is carried out in the base of an arbitrary criterion such as changes of colour and odour as well as the appearance of grounds[5].

The type of fat or vegetable oil used in the frying process is decisive, both from a sensorial and nutritional perspective of the resulting product, as well as from the point of view of yielding and economic cost. The frying oil will be part of the fried meals; therefore, the quality of fried foods greatly depends on it[5]. From a health point of view, in the last times an increased frequency of fried food consumption has been associated with different chronic disorders such as cardiovascular disease, heart failure, hypertension, type 2 diabetes or obesity. However, in the light of many studies these negative effects seem to be probably linked to the use of saturated oils for frying or to extreme frying conditions (temperature, duration) which lead to oxidation and then to increased amounts of trans-fatty acids[6]. In contrast, in some Mediterranean countries, e.g. Spain, where it is common to include the use of olive and sunflower oil for frying, this dietary pattern has been associated to a lower incidence of mentioned pathologies[7].

Frying is a typical way of cooking in the Mediterranean diet[8]. However, a worse adherence of the Spanish population to the Mediterranean dietary pattern has been observed in the last years[9,10]. In addition, the practice of this culinary technique has been recommended to be reduced in order to follow healthier habits. In 2005, the Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs of Spain approved the NAOS Strategy (Strategy for Nutrition, Physical Activity and Prevention of Obesity and Health) with the objectives of raising awareness of the problem of obesity and promoting initiatives that encourage a balanced diet and regular exercise. In this respect, the link between fried foods and a greater fat consumption together with the associated health problems has done frying the only culinary technique restricted from the NAOS Strategy and limited to a maximum of twice per week[11]. But the truth is that due to the current life style, fried foods have increased popularity because of its easy and fast preparation and their tasty appearance, that correspond to the wishes of the consumer.

On this framework, the aim of this work was to identify and evaluate the domestic deep-frying habits and consumer’s preferences in Spanish households with the purpose of detecting not recommended behaviours that could be re-educated in favour of healthier frying habits among the Spanish population.

Study design

The survey was designed by authors of the present study in consultation with colleagues from the Polytechnic university of Valencia. For the design, similar studies previously published were taken as a reference[12-14]. In a first step, the survey was piloted on 17 individuals through one-on-one interviews in order to identify specific focal points needed for the development of the questionnaire and to make the necessary adjustments based on respondent feedback. After that, the questionnaire was developed and validated with 35 subjects.

The survey included 32 questions divided into six different topics, according to i) socio-demographic characteristics (gender, age group, nationality, type of household, number of individuals/home and number of individuals lower than 18 years at home), ii) culinary habits (frequency of the appliance of different culinary techniques) iii) consumption and preparation of fried foods (frequency of consumption of fried foods and specifically of fried potatoes, fried doughs and breaded products; types of foods intended for frying (fresh or frozen) that are consumed, follow-up or not of the recommendations of frying, defrosting or not of frozen foods intended for frying), iv) frying oil characteristics (preference for the use of frying oils including oils labelled as special for frying, place of purchase and consumption), v) frying procedure characteristics (kitchen appliance used for frying, importance of frying temperature and control of it, subjective ratio between the amount of food respect to the dimensions of the frying utensil: less than half, half, more than half or full occupancy), vi) and after-frying habits (criterion to consider that food is fried (ready foods), method to remove oil from fried food, method to clean frying oil and place of storage of used oil). Questions were structured in check boxes with unique or multiple possible answers. In addition, dietary information and usual habits consisted of ratings of how frequently the individuals eat different types of foods, apply different culinary technics and use different frying appliance (daily, weekly, monthly, exceptionally and never). Questionnaire included a brief introduction about the aim of the study and participants gave their consent to use the data in the research.

Data collection

The present study was conducted using both web-based and paper-based questionnaires. Web-based survey was conducted via an internet platform through Google form links (Melbourne, Australia) and paper-based questionnaires were directly distributed to the respondents. Questionnaires were accepted when more than 75% of the survey was completely answered and no more than two questions per topics were missing. 281 responders were from the web-based questionnaires and 180 came from paper-based questionnaires. Both datasets were merged for analysis. The survey was conducted in May-June 2017. The criteria for selecting the participants were individuals who make or consume fried foods at home and whose ages were higher than 18 years. The main chains for the distribution of the questionnaires were schools, consumer associations, Universities, food associations, research centres, culinary centres, etc.

Statistical analysis

Responses collected from paper-based questionnaires were included in the Google forms and attached to those received by the internet form through this same online platform. In this way, the format of the output of the results was unified. All data were compiled in an excel spreadsheet format. Statistical analyses were performed using Statgraphics Centurion XV (Herndon, VA, USA) and SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics were used to describe all variables. Categorical data were expressed as frequencies and percentages.

Characteristics of the participants

This study provides information about the frying habits at Spanish households using data from a survey conducted to Spanish adults in May-June 2017. With the aim of obtaining representative samples of the study population and minimizing the introduction of response bias, the survey included both web-based and paper-based questionnaires[15]. The use of the web-based format allows a more broad dissemination of the questionnaires, with less-time and less costly. Another advantage is that returned data are already in an electronic format and complete information is received as it is necessary to fill the full test to be finalized and able to be sent. In order to avoid that data could come from a selective group, allowing only the participation of people who is accustomed to the use and who have access to internet, paper-based questionnaires were also distributed among participants. In this way, other collectives were included but with the risk that not all the questions are always totally answered.

A cohort of four hundred seventy five volunteers was randomly recruited for the cross-sectional population survey. Fourteen participants did not complete the paper-based questionnaire study and their data were withdrawn, then the number of participants responding the survey was 461. Two hundred and eighty one people filled out the online questionnaires and the rest completed the paper version. Participants were adults who usually prepare or consume fried foods at home. Most of them (58.6%) considered to have a high level of knowledge and experience in cooking. Between women, 66.1% considered they had high culinary experience, whereas only 46.3% of surveyed men considered themselves with such experience (data not shown). This finding was in agreement with the Spanish social pattern according to the information provided by the ENHALI-2012 study. This report displayed the differences in gender and the high participation of women in the activities of food preparation, confirming that 76.6% of women are responsible for all or most of foods cooked at home, compared to 21.8% of men[16]. Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, which are in line with the characteristics of the Spanish general population[17]. The final analysis included 175 males and 280 females consumers of fried foods, mostly Spanish (96.5%). Respondents were distributed across all age groups with 18-35 years (31.9%), 36-55 years (45.8%), 56-65 years (14.5%) and higher than 65 years (5.2%). The average profile of the households was constituted by two (27.3%), three (26.2%), 4 or more individuals (35.4%). Percentage of households with no individuals under 18 age was 60.1%. Regarding the type of household, majority of participants live in couple (61.6%), where a 39.0% live with children and the 22.6% without children at home.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

|

Characteristic |

Participants (%) |

|

Characteristic |

Participants (%) |

||

|

Gender |

|

|

Individuals / home |

|

||

|

Male |

175 |

(38.0) |

|

1 |

41 |

(8.9) |

|

Female |

280 |

(60.7) |

|

2 |

126 |

(27.3) |

|

Missing |

6 |

(1.3) |

|

3 |

121 |

(26.2) |

|

Age group |

|

|

|

4 |

127 |

(27.5) |

|

18-35 |

147 |

(31.9) |

|

5 |

27 |

(5.9) |

|

36-55 |

211 |

(45.8) |

|

More than 5 |

9 |

(2.0) |

|

56-65 |

67 |

(14.5) |

|

Missing |

10 |

(2.2) |

|

More than 65 |

24 |

(5.2) |

|

Type of household |

|

|

|

Missing |

12 |

(2.6) |

|

Single |

39 |

(8.5) |

|

Nationality |

12 |

(2.6) |

|

Single with children |

17 |

(3.7) |

|

Spanish |

445 |

(96.5) |

|

Shared apartment |

20 |

(4.3) |

|

Other than Spanish |

8 |

(1.7) |

|

Couple without children |

104 |

(22.6) |

|

Missing |

8 |

(1.7) |

|

Couple with children |

180 |

(39.0) |

|

Individuals < 18 at home |

|

|

|

Couple, children and relatives |

8 |

(1.7) |

|

Yes |

173 |

(37.5) |

|

With parents |

31 |

(6.7) |

|

No |

277 |

(60.1) |

|

With parents and siblings |

46 |

(10.0) |

|

Missing |

11 |

(2.4) |

|

Other situation |

5 |

(1.1) |

|

|

|

|

|

Missing |

11 |

(2.4) |

Culinary habits and description of the frying habits at home

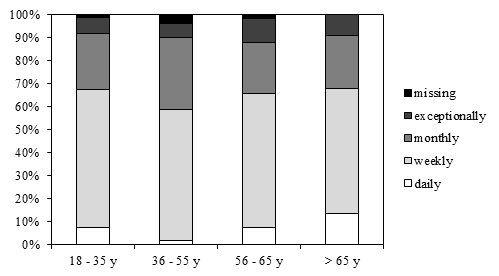

Results from the survey show that different culinary habits are well-distributed within the week. A 60.7% of participants declared the application of baking; 52.9% declared the use of boiling; 50.8% stated the utilization of frying; 46.9% mentioned the application of grilling and a 29.7% declared the use of steaming once or more a week (Table 2). Culinary habits more applied daily are cooking on the grill (42.5%) and boiling (39.0%). Frying is a common cooking method in Western countries and specifically is a typical way of cooking in the Mediterranean diet[8]. However, due to the proposed initiatives to prevent the problem of obesity, this culinary practice is recommended to be limited. The external causes of excess weight are several, but the inadequate diet and physical inactivity are emphasized because they are modifiable factors[18]. During frying, the food absorbs a part of the oil and increase the fat content and the caloric value. For that reason and despite its popularity, frying is the only technique culinary regulated in Spain from the NAOS Strategy (Strategy for Nutrition, Physical Activity and Prevention of Obesity and Health)[11]. From the present survey it is suggested that most people consume fried foods once or more a week (weekly) (58.6%) or once or more a month (monthly) (27.1%), whereas there were a low proportion of people who eat these products daily (5%) or exceptionally (6.9%). No relevant differences were found among age of the participants concerning the frequency of fried food consumption (Figure 1). The SUN (Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra) project described that university graduates in Spain consume fried foods with the following frequency: 0-2 times/week (41%), 2–4 times/week (33%) and more than 4 times/week (25%)[19]. Present results were similar not only to those found in other studies conducted in Spanish population but also in other nationalities with different culinary and food cultures. Cahill et al.[20] reported that US adult women and men mostly consume fried foods weekly and only 3.5% of women and 7.4% of men consume them every day. Similarly, Wang et al.[21] observed that fried foods were most frequently consumed 1-2 days per week (41.5%) or hardly at all (42.1%) in Chinese adult women and only 3.2% of the participants consumed fried foods nearly every day.

Table 2. Description of the frequent culinary habits, fried food consumption and habits for frying (participants and corresponding %)

|

Culinary habits |

||||||||||||||

|

|

daily |

weekly |

monthly |

exceptionally |

never |

|||||||||

|

Frying |

26 |

(5.6) |

234 |

(50.8) |

116 |

(25.2) |

82 |

(17.8) |

3 |

(1.7) |

||||

|

Baking |

17 |

(3.7) |

280 |

(60.7) |

115 |

(24.9) |

36 |

(7.8) |

13 |

(2.8) |

||||

|

Grill |

196 |

(42.5) |

216 |

(46.9) |

21 |

(4.6) |

15 |

(3.3) |

13 |

(2.8) |

||||

|

Boiled |

180 |

(39.0) |

244 |

(52.9) |

21 |

(4.6) |

7 |

(1.5) |

9 |

(2.0) |

||||

|

Steam |

43 |

(9.3) |

137 |

(29.7) |

73 |

(15.8) |

129 |

(28.0) |

79 |

(17.1) |

||||

|

Consumption and preparation of fried foods |

||||||||||||||

|

daily |

weekly |

monthly |

exceptionally |

missing |

||||||||||

|

Fried foods |

23 |

(5.0) |

270 |

(58.6) |

125 |

(27.1) |

32 |

(6.9) |

11 |

(2.4) |

||||

|

Fried potatoes |

13 |

(2.8) |

159 |

(34.5) |

146 |

(31.7) |

114 |

(24.7) |

29 |

(6.3) |

||||

|

Fried doughs |

1 |

(0.2) |

28 |

(6.1) |

41 |

(8.9) |

178 |

(38.6) |

213 |

(46.2) |

||||

|

Breaded products |

4 |

(0.9) |

115 |

(24.9) |

170 |

(36.9) |

120 |

(26.0) |

52 |

(11.3) |

||||

|

fresh |

frozen |

indistinctly |

|

missing |

||||||||||

|

Types |

216 |

(46.9) |

44 |

(9.5) |

195 |

(42.3) |

6 |

(1.3) |

||||||

|

|

yes |

no |

|

|

|

missing |

||||||||

|

Recommendations |

270 |

(58.6) |

123 |

(26.7) |

|

|

|

|

68 |

(14.8) |

||||

|

|

yes |

no |

depends |

not consumed |

missing |

|||||||||

|

Defrosting |

162 |

(35.1) |

205 |

(44.5) |

34 |

(7.4) |

6 |

(1.3) |

54 |

(11.7) |

||||

|

Frying oil characteristics |

||||||||||||||

|

sunflower |

olive oil |

both |

others |

missing |

||||||||||

|

Preference |

40 |

(8.7) |

316 |

(68.5) |

82 |

(17.8) |

1 |

(0.2) |

2 |

(4.8) |

||||

|

Place of purchase |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

neighborhood |

18 |

(3.9) |

29 |

(6.3) |

1 |

(0.2) |

4 |

(0.9) |

409 |

(88.7) |

||||

|

local markets |

13 |

(2.8) |

23 |

(0.5) |

1 |

(0.2) |

3 |

(0.7) |

421 |

(91.3) |

||||

|

supermarkets |

69 |

(15.0) |

143 |

(31.0) |

16 |

(3.5) |

4 |

(0.9) |

229 |

(49.7) |

||||

|

hypermarkets |

38 |

(8.2) |

119 |

(25.8) |

18 |

(3.9) |

3 |

(0.7) |

283 |

(61.4) |

||||

|

cooperatives |

1 |

(0.2) |

146 |

(31.7) |

0 |

(0.0) |

1 |

(0.2) |

313 |

(37.9) |

||||

|

|

yes |

no |

unknown |

|

missing |

|||||||||

|

Special for frying |

46 |

(10.0) |

275 |

(59.7) |

117 |

(25.4) |

|

|

23 |

(5.0) |

||||

|

|

< 2 liters |

2 – 5 liters |

>5 liters |

do not know |

missing |

|||||||||

|

Consumption |

320 |

(69.4) |

57 |

(12.4) |

9 |

(2.0) |

71 |

(15.4) |

4 |

(0.8) |

||||

|

Frying procedure characteristics |

||||||||||||||

|

|

frying pan |

electric fryer |

both |

other |

missing |

|||||||||

|

Kitchen appliance |

346 |

(75.1) |

22 |

(4.8) |

67 |

(14.5) |

7 |

(1.5) |

19 |

(4.1) |

||||

|

|

yes |

no |

|

|

|

|

missing |

|||||||

|

Temperature |

430 |

(93.3) |

11 |

(2.4) |

|

|

|

|

20 |

(4.3) |

||||

|

|

yes |

no |

|

|

|

|

missing |

|||||||

|

Tª control |

310 |

(67.2) |

129 |

(28.0) |

|

|

|

|

22 |

(4.8) |

||||

|

|

< half |

half |

> half |

full |

missing |

|||||||||

|

Potato/appliance surface |

56 |

(12.1) |

109 |

(23.6) |

170 |

(36.9) |

105 |

(22.8) |

21 |

(4.6) |

||||

|

After frying habits |

||||||||||||||

|

|

colour |

timekeeper |

without bubble |

smell |

missing |

|||||||||

|

Ready foods |

412 |

(89.4) |

13 |

(2.8) |

7 |

(1.5) |

3 |

(0.7) |

26 |

(5.7) |

||||

|

|

paper |

rack |

both |

none |

missing |

|||||||||

|

Removal of oil |

351 |

(76.1) |

33 |

(7.2) |

29 |

(6.3) |

22 |

(4.8) |

26 |

(5.7) |

||||

|

|

strainer |

paper |

both |

no reusing |

missing |

|||||||||

|

Cleaning |

248 |

(53.8) |

32 |

(6.9) |

4 |

(0.9) |

2 |

(0.4) |

175 |

(38.0) |

||||

|

|

same container |

closed container |

open container |

no reusing |

missing |

|||||||||

|

Storage |

61 |

(13.2) |

205 |

(44.5) |

80 |

(17.4) |

20 |

(4.3) |

95 |

(20.6) |

||||

Figure 1. Frequency of consumption or preparation of fried foods at home by age group (%)

Fried potatoes are the fried foods consumed more frequently (34.5% of participants consumed them once or more a week and 31.7% once or more a month). To a lesser extent breaded products are mainly consumed monthly (36.9%) and fried dough exceptionally (38.6%). Regarding the type of food intended for frying, most respondents (46.9%) considered they buy them fresh to prepare at home but also use both fresh and frozen or refrigerated foods (42.3%). In the case of foods prepared for frying, majority of people (58.6%) follow the frying recommendations indicated by the container. When frozen foods are consumed, most of the participants (44.5%) do not defrost the product before frying and 35.1% of them do it. A smaller percentage (7.4%) makes it depending on the food that is going to be fried. Only 1.3% declared not to consume frozen foods intended for frying.

The oil used for frying is part of the fried food that is consumed, therefore the quality of the fried foods depends to a great extent on the characteristics of the oil used. The choice of the frying oil is dependent on a number of factors, including price, stability and resistance of both oil and fried foods to oxidation. At high temperatures (150-200ºC), highly unsaturated vegetable oils have a short frying life and a short shelf-life due to their susceptibility to oxidation. In contrast, oils rich in saturated fatty acids or partially hydrogenated oils have improved stability profiles for prolonged frying[6]. In the present study, the use of olive oil to fry foods was reported by 68.5% of the subjects and 17.8% admitted to use both olive and sunflower oil. Other studies performed in Spain have also reported that the oil most used to fry at home by the Spanish population is olive oil[12,19,22]. Among the advantages of frying with olive oil, it should be highlighted the improvement in many cases of the saturated/monounsaturated/polyunsaturated fatty acid profile of the food and the enrichment of the food in fat-soluble vitamins and antioxidant compounds[23]. In this sense, although interest in the associations of dietary patterns and specific cooking techniques with risk of disease is increasing[24], in Spain, a Mediterranean country where olive or sunflower oil is used for frying, the consumption of fried foods is not associated with coronary heart disease or with all-cause mortality[22]. Present results are far from those found in a study conducted in Argentine adults, in which the oil most used to fry was sunflower, indicating the cultural differences between the two populations[13].

Regarding the reason for the choice of frying oil for the frying process, respondents admitted to be conditioned by the properties (280 subjects), taste (217 subjects), price (56 subjects) and stability of oil (50 subjects) but also by the type of food intended for frying (86 subjects) (data not shown). Very often, the choice of oil is also affected by the geographical location of consumer. Excluding the participants that reported missing data, survey displayed that frying oil is mostly bought at supermarkets (15.0% for sunflower oil and 31.0% for olive oil) and olive oil is also acquired in cooperatives (31.7%). These findings are in agreement with the general trends of the Spanish population, since people opt for large areas for the purchase of non-perishable products, which is done less frequently than fresh food. In contrast, the proximity trade of intermediate size and the small specialized shops (greengrocers, fishmongers, butchers and bakeries) adapt well to the needs of the Spanish diet, in which more than half of the expenditure is dedicated to fresh products[25]. Almost 60% of the participants are not consumers of oil labelled as "special for frying", even a quarter of the studied population was unaware of the existence of these oils. The majority (69.4%) usually consume less than 2 litters of frying oil per month.

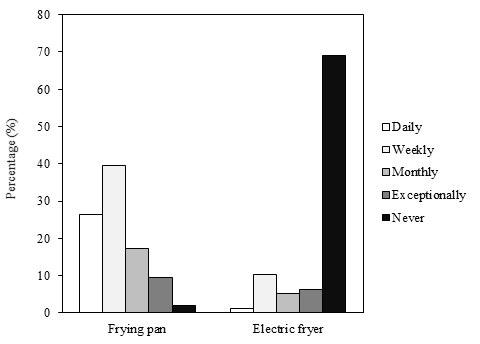

Among the frying procedure characteristics, the type of kitchen appliance selected for the frying process was evaluated in the questionnaire. Three fourths of the participants selected frying pan and only 4.8% marked the electric fryer as the preferred appliance. Moreover, 14.5% indicated to use both cookware indistinctly. The frequency of use of both utensils for frying is mostly weekly (Figure 2), in accordance with fried food consumption commented above. Another study conducted with Spanish students indicated that the selection of electric fryer or frying pan for the frying process depends on the product that is going to be fried. In this sense, electric fryer was mostly used to fry frozen and precooked foods together with potatoes, squid or homemade croquettes, while homemade frying of vegetables or fish is mainly carried out in frying pan[12].

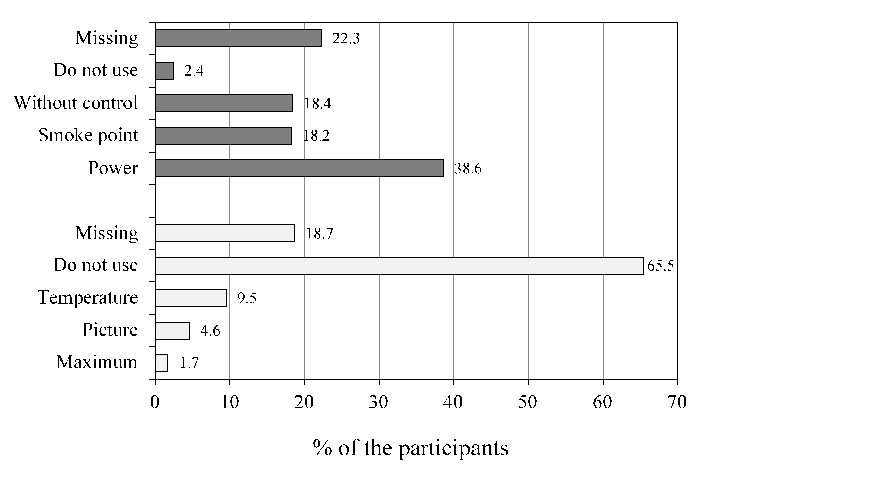

Figure 2. Frequency of use of frying pan and electric fryer to fry foods (%)

Majority of participants (93.3%) affirmed that they consider important to control frying temperature, although only 67.2% control it. Obviously, the way to control the temperature during frying will depend on the utensil used for the process (Figure 3). In the case of the frying pan, participants control the temperature mainly in three ways: i) by regulating the power of the gas flame, the glass ceramic or the induction plate (38.6%); ii) they consider that the temperature of the oil is adequate when it begins to smoke (smoke point) (18.2%) ;iii) they do not have precise control, pouring the food into the frying pan when the oil has warmed up for a while (without control) (18.4%). In the case of the electric fryer, the desired temperature is usually set: i) by controlling the thermostat according to the temperature considered that food needs (9.5%); ii) marking the picture of the food to be fried as indicated by the fryer (4.6%); iii) always selecting the maximum temperature independent of the type of food that is going to be fried (1.7%). Responders also indicated that according to the appliance surface, the amount of food intended for frying is mostly more than half of the dimensions of the frying surface (frying pan or frying basket) (36.9%) (Table 2). Information about the food/frying oil ratio was not reported.

At the end of the frying process, foods are considered to be ready because of the colour of the fried product (89.4%) and only a minority stop the procedure when timekeeper indicates certain time (2.8%), when the food stops bubbling in the oil (1.5%) or when the food smells like a fried product (0.7%).

Most of the participants (76.1%) use absorbent paper to remove the oil from fried foods. A 53.8% clean the oil used by filtering it with a strainer and storage it in a closed container (44.5%), in an open container (17.4%) or in the same frying container (13.2%) (Table 2). It has been reported that adults from Argentina have very similar habits, since they mostly use paper to remove excess oil from the food (84%), filter the oil before storage (52%) and store it in the same container (60%), in a glass container (20%) or in a plastic container (20%)[13].

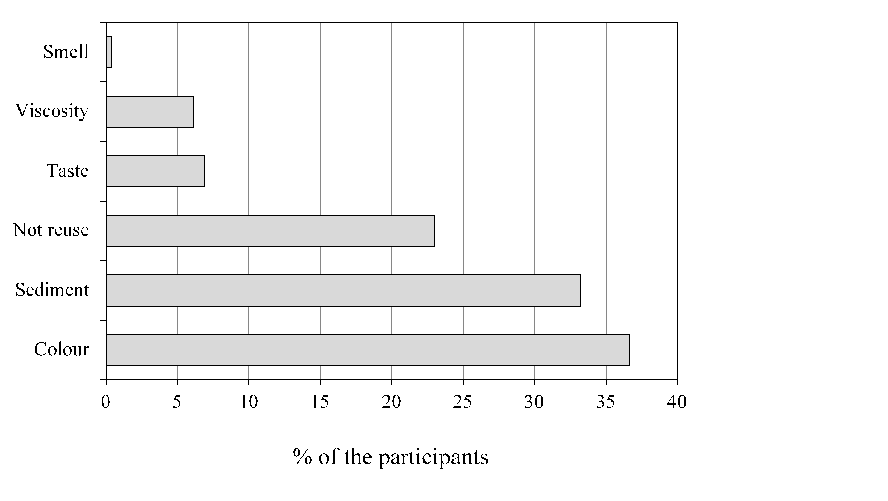

Figure 3. Temperature control during frying in the use of frying pan and electric fryer between the participants

An important factor is the times that frying oil is re-used. It is known that, with repeated use, oils deteriorate during frying, leading to a change in the fatty acid composition and absorption of other oil-degradation products into fried foods[26,27]. This fact may be more common away from home but also at home and, again, it depends on the appliance used for the frying process. Frying in a frying pan can be repeated a not very high number of times, given that the amount of oil is usually not much and the alterations in the oil appear soon. Using olive oil to fry in skillet up to 4-5 times can be an acceptable gastronomic and nutritional recommendation. Frying in an electric fryer uses a greater volume of oil and therefore the alteration products are more diluted allowing a greater number of frying[23]. In general, it could be advised to fry 10 times with sunflower oil and a little less than 30 with olive oil. These numbers could increase depending on the capacity of the fryer and the frying of lean foods[28,29]. The addition of "unused" oil to the fryer (refilling the oil that the food has adsorbed after each use) is a positive strategy from the nutritional point of view[28]. In the present study, among the frying pan users, a total of 53.4% of the participants reuse oil 2-4 times, a minority declare to reuse it 4-8 times (15%) and 6% do it more than 8 times. In contrast, 156 responders use fresh oil. Among the electric fryer users, the oil is re-used in a higher proportion: 4-8 times (38 participants), more than 8 times (30 participants) and 2-4 times (24 participants). It has to be taken into account that in the present survey, most of people selected frying pan as the common appliance used for the frying process. In this sense, students from Spain indicated that they usually change the oil from the electric fryer after the number of frying process, in the following proportion: < 5 times (9%), 5-10 times (21%), 11-20 times (25%), > 20 times(8%)[12]. Gatti et al.[13] reported that in Argentine, adults tend to reuse oil in the domestic practices once (28%), twice (40%), three times (4%) or until they see it is altered (28%), but in this study the used appliance is not specified. Factors considered by the participants as determinant for the change of frying oil are shown in Figure 4. As represented, main factors are colour of the oil (36.7%) and presence of sediments (33.2%) and in a lower proportion taste (6.9%), viscosity (6.1%) or smell (0.4%).

Figure 4. Criteria considered by participants as determinants for oil change

Findings from this study indicate that Spanish population mainly prepare or consume fried foods one or more a week, with a frequency close to that reported in other Western countries. As a typical Mediterranean habit, olive oil is the frying oil more used, followed by sunflower oil, which involves a healthy dietary pattern associated to a low incidence of cardiovascular diseases and other pathologies. Frying pan is the most common appliance for the frying process, promoting a more frequent change of oil (mainly based on its color change and the existence of sediment) and a greater control of the temperature. In contrast, the use of the electric fryer is less frequent and seems to be accompanied by the lack of control over this parameter. Fried potatoes are the most consumed fried food. Due to these products are a source of exposure to certain chemical process contaminants, such as acrylamide, it would be necessary to conduct future surveys focused on the frying habits of fried potatoes in order to detect those practices that may condition the presence of this acrylamide in these foods.

This research was funded by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Spain) under project SAFEFRYING (AGL2015-46234-R). Authors thank Dr. J. Martinez-Monzó and Dra. P.García for the validation of the questionnaire.

Stier, R. F. (2004). Frying as a science – An introduction. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology, 106, 715–721.

View ArticleGertz, C. (2014). Fundaments of the frying process. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology, 116, 669–674.

View ArticleCabreriso, M. S., Chain, P., Gatti, M. B., & Ciappini, M. C. (2017). Cambio químicos y sensoriales producido en aceite de girasol y de oliva extra virgen en el proceso de fritura doméstica. Diaeta, 34, 22–28.

USDA (2012). Deep Fat Frying and Food Safety. Food Safety Information. / Accessed 20 July 2018.

View ArticleValenzuela, A., Sanhueza, J., Nieto, S., Peterson, G., & Tavella, M. (2003). Estudio comparativo, en fritura, de la estabilidad de diferentes aceites vegetales. Aceites y Grasas, 53, 1568–1573.

Gadiraju, T.V., Patel, Y., Gaziano, J. M., & Djoussé, L. (2015). Fried Food Consumption and Cardiovascular Health: A Review of Current Evidence. Nutrients, 7, 8424–8430.

View ArticleGarcia-Lopez, M., Toledo, E., Beunza, J. J., Aros, F., Estruch, R., Salas-Salvado, J., Corella, D., Ros, E., Covas, M. I., Gomez-Gracia, E., Fiol, M., Lamuela-Raventós, R. M., Lapetra, J., Buil-Cosiales, P., Carlos, S., Serra-Majem, L., Pintó, X., Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V., & Martínez-González, M. A. (2014). Mediterranean diet and heart rate: The predimed randomised trial. International Journal of Cardiology, 171, 299–301.

View ArticleBastida, S., & Sánchez-Muniz, F. J. (2015). Frying: a cultural way of cooking in the Mediterranean Diet. In V. R. Preedy, & R. S. Watson (Eds.), The Mediterranean Diet. An evidence-based approach. London, UK: Academic Press.

Grosso G, Marventano S, Giogianni G et al (2013). Mediterranean diet adherence rates in Sicily, southern Italy. Public Health Nutr 17, 2001–2009. PMid:23941897

View Article PubMed/NCBIBonaccio M, Di Castelnuovo A, Bonanni A et al (2014). Decline of the Mediterranean diet at a time of economic crisis. Results from the Molisani study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 24,853–860. PMid:24819818

View Article PubMed/NCBIMinisterio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad (2005). Agencia Espa-ola de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición (AESAN). Estrategia para la Nutrición, Actividad Física, prevención de la Obesidad y Salud (NAOS).

Romero, A., Cuesta, C., & Sánchez-Muniz, F. J. (2001). Utilización de freidora doméstica entre universitarios madrile-os. Aceptación de alimentos congelados fritos en aceite de oliva virgen extra, girasol y gisarol alto oleico. Grasas y Aceites, 52, 38–44.

Gatti, M. B., Cabreriso, M. S., Chain, P., Coniglio, A., Manin, M., & Ciappini, M. C. (2015). Evaluación de la frecuencia de consumo de alimentos fritos y de las técnicas de frituras doméstics en adultos rosarinos. Invenio, 19, 155–165.

Wood, K., Carragher, J., & Davis, R. (2017) Australian consumer's insights into potatoes - Nutritional knowledge, perceptions and beliefs. Appetite, 114, 169–174. PMid:28363811

View Article PubMed/NCBIVan den Berg, M. H., Overbeek, A., van der Pal, H. J., Versluys, B., Bresters, D., van Leeuwen F. E., Lambalk, C. B., Kaspers, G. J. L., & van Dulmen-den Broeder, E. (2011). Using web-based and paper-based questionnaires for collecting data on fertility issues among female childhood cancer survivors: differences in response charcteristics. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13, e76.

View ArticleDíaz Méndez, C., García Espejo, I., Gutiérrez Palacios, R., & Novo Vázquez, A. (2013). Hábitos alimentarios de los espa-oles. Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente. PMCid:PMC3734154

INE (2017). Instituto Nacional de Estadística. / Accessed 20 July 2018

View ArticlePérez, C., Aranceta, J., Serra, L., Moreno, L., & Delgado, A. (2006). Epidemiology of obesity in Spain. Dietary guidelines and strategies for prevention. International Journal of Vitamin and Nutrition Research, 76, 163–71. PMid:17243078

View Article PubMed/NCBISayon-Orea, C., Bes-Rastrollo, M., Basterra-Gortari, F. J., Beunza, J. J., Guallar-Castillon, P., de la Fuente-Arrillaga, C., & Martinez-Gonzalez, M. A. (2013). Consumption of fried foods and weight gain in a mediterranean cohort: The sun project. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Disease, 23, 144–150.

View ArticleCahill, L. E., Pan, A., Chiuve, S. E., Sun, Q., Willett, W. C., Hu, F. B., & Rimm, E. B. (2014). Fried-food consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease: a prospective study in 2 cohorts of US women and men. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 100, 667–675.

View ArticleWang, F., Wang, F., Yu, L., & Yu, Z. (2017). Dietary choice and health behaviors in eastern Chinese women: a descriptive, population-based survey and review of public health data. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 26, 561–570. .

View ArticleGuallar-Castillón, P., Rodríguez-Artalejo, F., Lopez-Garcia, E., León-Mu-oz, L. M. Amiano, P., Ardanaz, E., Arriola, L., Barricarte, A., Buckland, G., Chirlaque, M. D., Dorronsoro, M., Huerta, J. M., Larra-aga, N., Marin, P., Martínez, C., Molina, E., Navarro, C., Quirós, J. R., Rodríguez, L., Sanchez, M. J., González, C. A., & Moreno-Iribas, C. (2012). Consumption of fried foods and risk of coronary heart disease: Spanish cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition study. British Medical Journal, 344, e363.

View ArticleSánchez Muniz, F. J. (2007). Aceite de oliva, clave de vida en la Cuenca Mediterránea. Anales de la Real Academia Nacional de Farmacia, 73, 653–692

Astrup, A., Dyerberg, J., Elwood, P., Hermansen, K., Hu, F. B., Jakobsen, M. U., Kok, F. J., Krauss, R. M., Lecerf, J. M., LeGrand, P., Nestel, P., Risérus, U., Sanders, T., Sinclair, A., Stender, S., Tholstrup, T., & Willett, W. C. (2011). The role of reducing intakes of saturated fat in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: where does the evidence stand in 2010? American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 93, 684–688.

View ArticleMAGRAMA (2012). Panel de consumo alimentario (varios a-os), Madrid, Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente.

Fillion, L., & Henry, C. J. (1998). Nutrient losses and gains during frying: a review. International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition, 49, 157–168.

View ArticleChoe, E., & Min, D. B. (2007). Chemistry of deep-fat frying oils. Journal of Food Science, 72, R77–86. PMid:17995742

View Article PubMed/NCBISánchez-Muniz, F. J. (2005). El aceite en la cocina. Normas para un uso adecuado. In J. A. Pinto Montanillo, & J. R. Martínez Álvarez (Eds.), El aceite de oliva y la dieta mediterránea. Nutrición y salud (pp. 67–76). Vol. 7. Alcobendas, Madrid: Servicio de Promoción de la Salud. Instituto de Salud Pública. Dirección General de Salud Pública y Alimentación. Consejería de Salud y Consumo.

Sánchez-Muniz, F. J., & Bastida, S. (2006): Effect of frying and thermal oxidation on olive oil and food quality. In J. L. Quiles, M. C. Ramírez-Tortosa, & P. Yaqoob (Eds.), Olive Oil and Health (pp. 74-108). Oxfordshire, UK: CAB International.

View Article